On Mahatma Gandhi’s 150th birth anniversary, UNESCO Chair in Community Based Research and Social Responsibility in Higher Education in partnership with International Development Research Centre (IDRC), UNESCO New Delhi Cluster Office and Association of Indian Universities (AIU) hosted a two-day international dialogue on Gandhi and higher education. Titled “Educating the Mind, Body and Heart”, the intercontinental dialogue brought together practitioners, academicians and Gandhian philosophers to explore the contemporary relevance, applications and impact of Mahatma Gandhi’s theory and practice on higher education in India and the world.

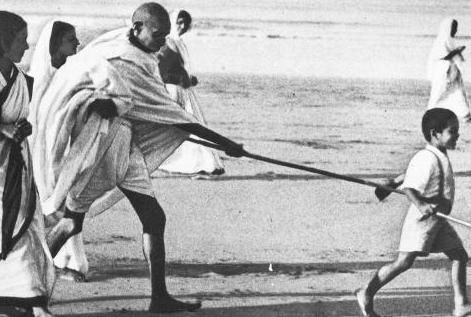

Gandhi is known in different circles for his different statures. He was an activist, a leader, a philosopher, a philanthropist, but his work as an educator is perhaps the most overlooked facet of his life. Gandhi had written, spoken extensively about the importance of education and learning. India with the rest of the world will celebrate the sesquicentennial birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi next month, and the relevance of Gandhian principles in rethinking higher education has never been greater than today.

Of the many perspectives and conversations that emerged out of this Dialogue, we have gleaned some of the key insights that stand to deepen our understanding of Gandhi and Higher Education and a few innovative methods of assimilating his principles in advanced pedagogy.

Exploring the contemporary relevance of Gandhi’s perspectives and approaches to higher education today

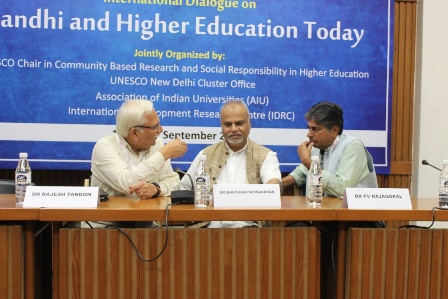

Reflecting on Gandhi’s teachings, UNESCO Co-Chair Dr. Rajesh Tandon invokes the titular wellspring. “As Gandhi said ‘Universities do not need a pile of majestic buildings; University needs intelligent backing of public community.’ Igniting the discussion further, he added that in the last seventy-eighty years, the walls of higher education have only increased in height and width, not necessarily secured the backing of intelligent public opinion that Gandhi talked about.” This later resonated in Prof. Catherine Krull’s thought-provoking question, asking what it means to be an educated person in the 21st century, and set the note for the dialogue that ensued.

For UNESCO Regional director Mr. Eric Falt, the dialogue was extremely pertinent and timely. “There has never been a greater need to look at education from a new perspective, one that will question and clarify the fundamental motivations that drive systems and practice of education so that education remains relevant to the needs of learners and the changing learning environment,” he said invoking the ramifications of the new National Education Policy recently tabled and currently under deliberations by the Indian government. At a global level too, there is ongoing debate on “how education needs to be rethought in a world of increasing complexity, uncertainty, and precarity.” This thought was further fueled by Dr. WG Prasanna Kumar, an eminent Gandhi practitioner who re-explored Gandhi’s educational reforms of Nai Taleem and the merit it offers to contemporary education by bridging the gap between theory and practice in Indian pedagogy; he demonstrated this praxis with real life teaching pedagogies and examples from his own university: Mahatma Gandhi National Council of Rural Education (MGNCRE).

Reviving the virtues of Non-violence and Peace in education

Discussion on both days veered towards bringing back the virtues of peace and non-violence in higher education as well amongst the youth. “Concepts such as non-violent economy and non-violent governance must replace the present development paradigm modelled on war, crime and violence. There is a lot of research, innovation and investment in the war industry. There is a need to bring the same into non-violence,” said Dr. PV Rajagopal, eminent Gandhian practitioner. While sharing his learning curve from local to global knowledge, he also posed an important question for young academics: “How can our education be made relevant to today’s world, especially for the marginalised?” . It was further appended that Gandhian principles of “knowledge of the people, for the people”, the transformative power of non-violence, and the tenets of ahimsa incorporated in higher education training and learning provide us pathways for the future.

This sentiment was later echoed by UNESCO Co-Chair for Peace and Intercultural Understanding Professor Priyankar Upadhyay in his treatise on the various strands of peace studies practised in India, where “despite Gandhi, everything he abhorred like nuclear weapons exist.” Prof Upadhyay underscored the need to bring about a new dimension to research in conflict resolution saying, “Peace studies is entirely experiential,” urging academics to explore structural violence and look at the role of cultural and religious diversity in bringing peace.

Similarly, IDRC’s Asia director Dr. Anindya Chatterjee noted that the Mahatma was a proponent of change and experimentation while being thoroughly committed to his core beliefs like self-determination and nonviolence and emphasized on re-instilling the same virtues in individuals and institutions today.

Learning rooted in reality

“Gandhi believed in holistic education, not separating one from the other,” Dr. Rajesh Tandon, UNESCO Co-Chair in Community Based Research, said in his opening note explaining the rationale behind the title of the event. He stressed on the need for lifelong learning from and within society to bridge menial and mental labour, also challenging the dichotomy between knowing and doing that has insulated academia. As the esteemed speakers each presented a blueprint for alternate methods of knowing and doing, it soon became clear that the Gandhi’s vision — higher education should produce experts who are relevant for society’s needs —if university education occurs in tandem with Gandhi’s notion of karma.

Vice Chairman of University Grants Commission (UGC), Dr. Bhushan Patwardhan, highlighted how universities have monopolized the education system and undermined knowledge creation outside the classroom. “Teaching as dialogue, which has been so in Indian tradition, encourages courageous, bold questions and equally bold answers,” he said. The initiatives taken by the UGC like ‘Trans-Disciplinary Research in India’s Developing Economy’ to study real problems with a special focus on social impact projects will offer students an opportunity to work with the community, he added.

In the last leg of the dialogue, Dr. KK Aggarwal, Chairman, National Board of Accreditation (NBA) and former Vice Chancellor of Guru Gobind Singh (GGS) Indraprastha University gave a striking metaphor of integrating the mind, body and heart in learning technical courses like engineering. He stated that students of technical education should also be taught music, maths and gymnastics to integrate heart, mind and body and thus ensure a holistic learning.

Innovations in higher education through social responsibility and community engagement

“I don’t see the idea of innovation in isolation. Your knowledge and actions should benefit your local community,” said Dr. Albogast Kilangi Musabila from Tanzania, one of the international delegates who spoke at the international dialogue. Thousands of miles away in India, this philosophy at the centre of the Gandhian school of thought was already in practice at the Dayalbagh Educational Institute near Agra.

Dr. Anand Mohan, Registrar of Dayalbagh University, shared its vision to empower the weakest sections of society, build economy through frugal innovations, achieve more with less, and contribute to better worldliness. He was also pleased to announced that community participation by the students has led to afforestation and cultivation over large swatches of fallow land in Dayalbagh through practices such as organic farming, reclamation of wasteland, safe disposal of garbage and irrigation using water from DEI’s government-funded sewage treatment plant. “No groundwater is exploited and most of the power is sourced from the local solar grid; the produce is mostly consumed and surplus water is shared with neighbouring villages — this sustainable development has transformed the area into an eco-habitat.”

Speakers from various disciplines and countries also spoke for the revival of peace studies, community engagement, indigenous research methods and knowledge systems, value-based education, and sustainability studies, all of which finds a place in Gandhi’s Nai Taleem, an alternative form of learning he propounded and practised nearly a century ago.

Professor George L Openjuru, Vice Chancellor of Gulu University in Uganda, spoke of “producing knowledge that makes life better”. Dr. Catherine Krull, Special Advisor to the Provost of the University of Victoria, Canada, advocated the need for inclusion of community engagement in mainstream education. She presented key education policies and schemes in Canada that support community engaged learning. Professor Andrea Vargiu, from the University of Sassari, Italy, discussed the myriad possibilities of policy convergence in deepening engaged teaching and research, with special attention to the production and organisation of knowledge.

Dr. Crystal Tremblay, community activist and professor of geography at the University of Victoria, shared her vibrant journey working alongside the indigenous Lekwungen people of Canada, listing some of the core principles of indigenous research that can be traced back to the relational and holistic aspects of Gandhian ideas like nurturing a spiritual relationship with land and water. Dr. Darren Brendan Lortan from Durban university of Technology spoke with a resounding belief that participatory processes are equivalent to nonviolent forms of protest. Ms Kanyakumarie Padayachee explored in her paper, the linkages between and the postcolonial relevance of Gandhi’s teachings and Ubuntu ways of knowing and doing.

The final leg of the dialogue witnessed invigorating discussions among all the participants of the dialogue as four education practitioners from Indonesia, Malaysia and Tanzania offered their diverse policy perspectives and innovative practices inspired by Gandhian principles, including religious studies, environmental humanities, continent engagement, multilingualism with a primary focus on native languages, interdisciplinary curricula, developing sustainable employment opportunities and corporate social responsibility – with a concerted and unanimous pledge to revive indigenous knowledge systems.

Gandhi and Knowledge Democracy

Striking a hopeful chord, UNESCO Co-Chair Dr. Budd Hall reminded those gathered of their peers around the world, engaged in important work in bringing community knowledge into the classroom to finding solutions to issues ranging from climate change to gender discrimination. He made the critical observation that universities, just like corporations, the state and the church, were sites of contestation.

The Knowledge for Change (K4C) program is one such platform that allows vibrant contestation while staying committed to bringing positive changes to the society we are a part of. He also voiced the need in this regard, to overthrow the culture of epistemicide and to decolonize knowledge systems from western hegemony with the help of Gandhian teachings relevant to the contemporary world. The UNESCO Co-Chairs also took the opportunity to award three graduating mentors their professional qualification certificates.

In his closing address, Dr. Tandon highlighted the disconnect in modern education that renders students unable to apply the concepts that they study to reality. Marveling at how far we have regressed in the name of progress, he highlighted the power imbalance between those who do and those who know. To ensure that knowledge is no longer accumulated in the hands of the privileged few, we must switch to community-based lifelong learning, he said. Placing the onus on traditional knowledge systems one last time, Dr. Tandon signed off with an important reminder: “If you devalue your own knowledge, you won’t be powered to accept new knowledge.”

For more information about the conference, Knowledge for Change (K4C) program and the work of the UNESCO Chair in Community Based Research and Social Responsibility in Higher Education, please contact Pooja Pandey (pooja.pandey@pria.org).